Susan Kennedy has spent the past 30 years devoted to sparking joy and creativity within San Francisco children. She became actively involved in working with public school students when her two sons attended the then-named Dr. Charles R. Drew Alternative Elementary School (Drew) in the ‘90s. When she saw that they had no general music program, Susan, who was training in the Orff Schulwerk approach to teaching music and movement, developed an Orff program for 1st through 5th graders at Drew. During her five years as the Orff teacher at Drew, the students explored creative expression through moving and playing the Orff instruments. She continued as a volunteer for two additional years, directing Drew’s Orff ensemble, which performed in school programs and for public events and conferences.

Susan’s path took her to teach at an independent bilingual school for 22 years, but she found her way back to Drew last year as a volunteer with the SF Ed Fund. She assisted 4th graders with their math, and, with the support of the lead teacher, she introduced projects that address mathematical thinking through sound, movement and design. One of these projects was planning and weaving potholders. We interviewed her to learn more about her experience, and to understand how this handwork not only improves physical abilities, it improves mental abilities. As Susan explained to students’ parents, “Working with hands + making patterns = better brains!”

SFEF: Can you tell us about your back-story and your experience as a teacher?

SK: I earned Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees in Dance during the ‘70s, performed and did some college teaching. I thought I wanted to teach adults but I also wanted to do something that felt more grounded and egalitarian. As soon as I started working with kids, I was so delighted with how creative and out-of-the-box their thinking was; compared to the adults I had taught, children were so fresh and just wonderful. My experiences teaching at Drew in the ‘90s had been life-changing, so after I retired from full-time teaching, I wanted to see if there might be a way to go back and contribute to Drew. Last year, I saw [an SF Ed Fund volunteer listing] for Charles Drew to help with fourth grade math. I love 3rd and 4th grade – so I met the teacher; we connected really well and I walked away feeling excited about the possibilities.

SFEF: One project of yours this school year was teaching 4th graders at Charles Drew how to weave potholders by incorporating math into the planning. Can you tell us more about this project and your inspiration to take it on?

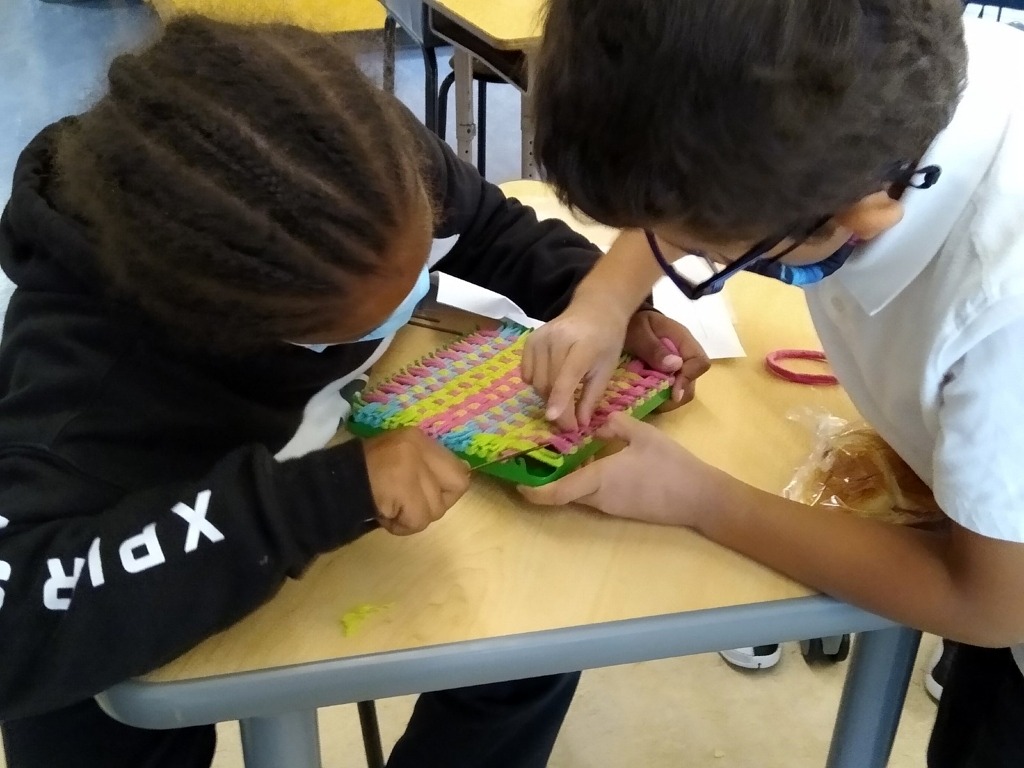

SK: As an Orff teacher, I am always thinking about the integration of our brain hemispheres and how so many music and movement activities are good for that. When I started working with the 4th grade class at Drew, even though I wasn’t acting as a music teacher, I thought about the potholder idea because of the different kinds of mental activities [needed] to carry it out: the obvious math (taking three colors and figuring out different ways to create patterns with colors), and the motor experience of doing the weaving.

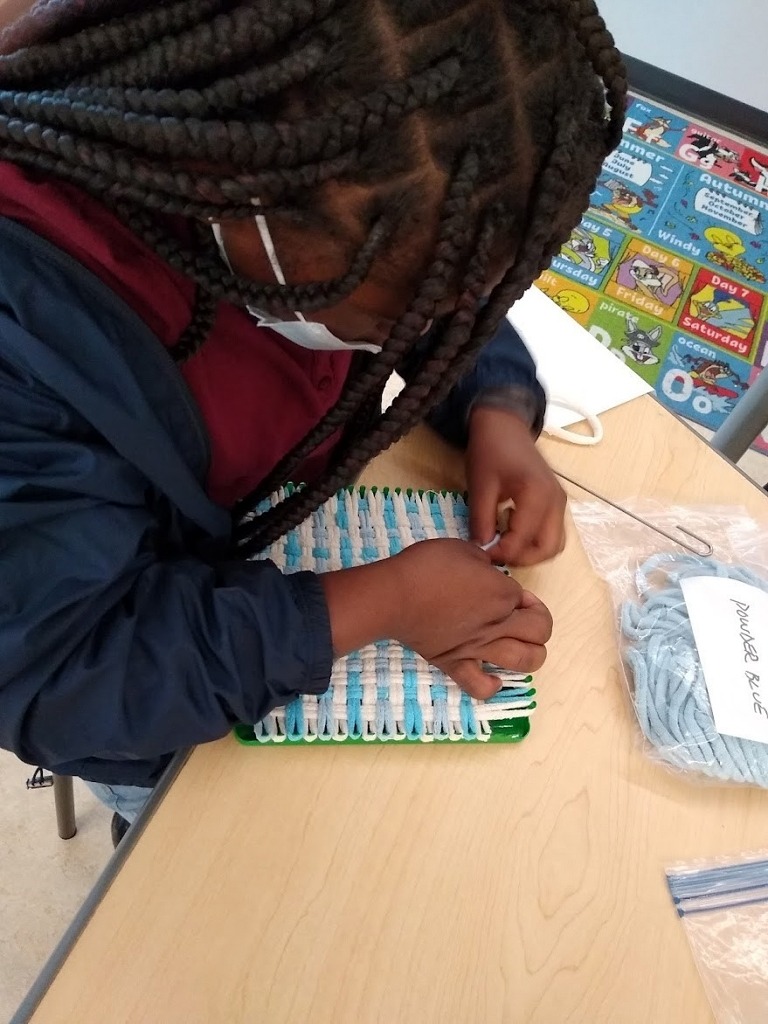

Many children’s nervous systems are rather unregulated; they benefit from doing something regular and repetitive. Weaving is a therapeutic activity. During and after World War I, to help the men who were injured and who had post-traumatic stress, therapists had them doing handwork such as weaving, working with clay, and wood carving. Doing handwork is an occupational therapy strategy. Weaving benefits fine motor skills, and also cognitive skills like planning, organizing, frustration tolerance, and problem solving. I saw that happen with all of the children I worked with. When they saw they had made a mistake, they had to undo it, redo it, and keep persevering to complete it.

After I finished the potholder project with the 4th graders, the 3rd grade teacher asked me to repeat the project with his students. I knew they would need more preparation, so we did a preliminary session with paper weaving to make sure they could get the over-under weaving idea, visually and physically. When I started weaving with this younger class, they were very vocal and got discouraged easily. Then, over the hour, they settled down and got to work. Once they got the weaving technique and were excited about the designs, [the transformation] was really awesome. They felt gratified and in command.

SFEF: How do you get a sense this is sparking an interest in math?

SK: This is an opportunity to put math into action; recognizing patterns is very central to mathematical thinking. For this, the students pick three colors out of 33 available and invent a pattern totaling 18 across the top and 18 down the side. I made a worksheet for them to plan it out with their three colors. We figured out how to find the factors of 18 (1, 2, 3, 6, 9, 18) which then gave them ideas about how to make their patterns of colors. . They need to have these experiences on an almost daily basis for it to affect their brains.

Another exercise we used in this project was creating percussion patterns. I brought three hand drums to the school and invited the students to “read” the three colors in the potholder patterns with the drums by assigning a different drum to each color in the sequence. To prepare that idea, we used body percussion — clap, pat, and stamp — so the whole class could do it together. Some people learn better with their ears; the potholder project was a way to see the pattern, make the pattern with their hands, and hear the pattern.

We should always be trying to reach the kinesthetic learners because they’re the ones who are really neglected in our schools, the ones who are not linguistic or visual learners. For some kids, that’s not how their brain works. Music and movement help reach other important parts of the brain to help them learn. This project certainly resonated with some students more than others; some students have begged me to make more. I added another lunchtime session for kids who wanted to do more advanced design work.

SFEF: What role do you see volunteers playing in classrooms? What becomes possible for students and teachers when there is a volunteer?

SK: It depends on the volunteer – sometimes a volunteer comes in and gives one-to-one support, other volunteers have full class projects they want to lead. If the teacher gives us the space, some volunteers can implement full projects. I’m coming in with years of experience teaching kids, and other people will come in having worked in the tech industry or from other careers, with so many gifts to share. To make it work, there needs to be great communication between the teacher, volunteer and principal. But every volunteer has their own unique contribution.

The San Francisco Education Fund matches students in our partner elementary and middle schools with literacy, math, or mindfulness tutors, and mentors. We also match teachers with classroom or general volunteers. These volunteers are caring advocates that help students accelerate learning to get on grade level proficiency or lend teachers a helping hand. You could join a team of caring adults who are supporting students in a meaningful way. If you’re interested in volunteering for the 2022-23 school year, please fill out this form and you’ll receive the volunteer application in July.